I left the dorms at a jog, quietly letting each foot fall to the pavement as it chose, not rushing the strides or their pace. The air was cool and sharp, free from the humidity of summertime and still resisting the bite of early winter breezes. The sun had begun its fall - its fall fall that is - an early, sort of sideways jaunt toward the horizon that seems to be going away for hours - but would sustain the shadows and their chill for a few more hours. I could not run the loop today. I would not run the loop today.

I turned down Commonwealth Avenue instead, preferring the beat of the moving world, its car horns and train screeches, cell phone rings and laughter to the strange pseudo-nature of the reservoir. The pace was determining itself, and I began to look around. People moved back and forth to school, the traffic moved in spurts of red and green behind me, the urbanized wildlife chittered in the trees. Tiles of pavement passed beneath me, concrete dotted with iron, the covers of the inner workings of the material world. Lightposts towered above me, wires lined the streets. And as I passed, I was most likely picked up on the security cameras of several different dwellings and businesses, a moving blur captured forever in static motion, in that one second of passing, like a ghost image in an under-developed photograph.

Down past the intersection, which I avoided, cutting across the marked lanes of the road and dodging delivery trucks, flashers on in that great, semi-acceptable gesture of double-parking we New Englanders love the most and hate the worst. A matter of perception, point of view, and time until the liquor store closes. Down beacon street, left side for a block. Within half a mile of the Circle the housing gets expensive. The feet keep moving, still of their own accord, and the light that filters down through the barely green trees reflected off my sunglasses and bathed my eyes in the glowing amber of late afternoon. I crossed the street, newly paved and lined, the thick black pavement unaffected by its first winter, the granite sidewalks not yet subjected to their first early November frost heave. Across the train tracks. One way.

The first row of apartments quickly give way to the hidden Eden of residential Boston, the gems just off the street that could be placed in middle American suburbia if not for their price tags and cordoned yards. The cars lined along the side look out of place in this more pastoral environment, the large ones even more so. Who lives here? I see a young mother pulling a stroller out the front door of a home on the left - a modest home, with light blue trim and a small but well-maintained garden posted up before the front windows, a model of Renaissance symmetry transplanted 500 years. An older gentleman in a grey suit, trousers hemmed high in the style of the recent past, bowler cocked on his head in the style of the not so recent past. He walked, as I ran, in the dead center of the street, and we moved slightly to our respective right hands as we passed, exchanging a brief, cordial head nod. We were, on foot, both an affront to the motor vehicle-centric infrastructure on which we travelled, and I suspect we both did it for the same reasons - because on this sunny day we could.

The street came to dead end and I looked for a way out, legs still pumping alternately and aloof below me. Cutting through a park, I passed a couple playing tennis, another couple walking slowly with their groceries, she with a beautiful red and gold cloth covering her head and he with a subtle black yarmulkah carefully placed upon his salt and pepper hair. Climbing the stairs on the far side of the park two young black men coach and instruct a group of youngsters in an after-school program, hopping up the hill like frogs. The top of the stairs brought more fresh pavement and yellow-white lines, a new set of stoplights, and the general pervasiveness of high-end autos. I crossed the street onto Beaconsfield road, a winding, traffic-less, residential street with homes that towered above on the left and fell off below to the right. I could be anywhere, I thought, and find a road like this. A small Vermont town might have a small cabin like the one beside me, the tall Victorian ahead could be stamped on a corner in Indiana, the split level ranch coming up on my right stood somewhere next to its brethren in the heart of Pennsylvania or Ohio, and the saltbox 1950's pre-fab was a clear refugee from the West coast suburbs that dotted California, Arizona, and New Mexico. But this was Boston, and the clank of my right foot on a sewer lid reminded me of the municipal system that lay beneath and above the pavements.

Three more miles down, as the crow flies, and I'd be in Roxbury, running through abandoned lots, fast food restaurants, bodegas, and tenement housing. I turned left, up and away from the city proper and chugged up a small hill to the street that would lead me back to the black arteries of asphalt that tied all to the center, converging on the crotch of the system, the Pike/93 confluence, South Station, Government Center. All of the major roads lead here, find some intrinsic connection to the movement of goods and services and labor. But between them, in the gaps between the restraining belts of Beacon and Commonwealth and Boylston, were myriad twisting, turning, poorly paved streets and convoluted infrastructures. You can get lost in these strange conflations of one-ways and cul-de-sacs, cut-throughs and alleys, parking lots that work as streets and vice-versa. I recommend it. To be turned around in a city, bounded by thoroughfares and abandoned by street signs, is a remarkable experience, and a valuable one.

There is a direction to the madness, a general understanding on my part that I know where I am going and where I will end up. But the path is uncertain, and by no linear means will I arrive back at the starting point. These uphill, downhill, curving stretches of road, now turning through the residential alcove that hides between Beacon and Commonwealth, will guide me back through this maze of sunlight and green air, back to those places I know well, taking me back in memory even as they take me forward in the present. The feet keep moving, the pace is fine, and though the chest heaves higher and further from rest there is catharsis to this movement, the energy I've consumed coming back to me in fluid motion - left, right, left. Up on my right there is a gingerbread house with frill yellow trim set against a sky blue exterior and a bright red door. And on the steps of this 18th century Victorian are two kids, both in jeans and skeakers, both sporting Red Sox hats, one over his tight-cropped, curly black hair and deep skin, the other over blond swatches and freckles. The sun sees them both the same, they see each other as peers, and luckily, on this afternoon, no one else sees them at all. Two massive oak trees mark the corner of the block and cast shadows over the stop sign in diagonal relief. I turn right, onto the sidewalk for a moment until the traffic clears and I run sideways across the lines, white then yellow yellow and white again, off the next side street and up, sloping, towards the backside of Comm Ave.

The streets get even dicier here, and I find myself tangled in a maze of parking Do's and Do Not's, mangled in the concrete and steel infrastructure of ill-planned condo complexes and one-way driveways that lead to nowhere. A block further and the image of the VIctorian with its artistic aesthetic, gated yard, and flora is gone altogether. Bricks dominate my view, perched in staggered row after row to form massive square boxes with glass portholes to keep the prisoners' hope alive. I can't make out who might live here, or how they found this place to live, or decided that this was what their life would be. And I can't tell for sure that I won't be in a similar situation in the months to come, untethered, lost between the selves I knew very well at one time and the self I am beginning to understand anew with each block and each step and each passing minute. I am here, actively, and yet here passively, too - caught once again in the intersections of time-space and thought-memory, doomed to overanalyze even as I move with the most concrete motion. Up, down, up, down. Left, right. Left.

And I come up between two buildings, pass a cable company van and a screaming cab driver, wind passing over my ears, bringing the sounds rushing to the center of my brain and me rushing back to the center of this sensory, sensational experience. Just a run on a Tuesday afternoon in Boston. Just the movement of my feet on the pavement, trapesing through the turbulent middle of a city without a center. I can hear the first clicks and turns of the T, the medieval screech of an outdated transportation system whose convoluted design barely outpaces the spiderweb of pavements, some named and some not, that constitute a quaintly archaic infrastructure. There is no method to the madness other than madness itself, and yet as I dodge Range Rovers and Priuses hauling ass on the backs of fossil fuels I am comforted by the ability to make journeys of un-straight lines that still lead me back to the known world. And I am convinced, once again, that there is an appreciable difference between being lost and not knowing where you are going. I am going forward, and sideways, and backward all at once, but there is only one motion involved, the simple corporeal stepping of my feet beneath me and my heart within me. So I will take these tools to be my own as I skip past South St, a place I once knew well that has forgotten me now. And I cross the train tracks a last time as the confines of the campus coming running towards me even as I remain running away from them, a mere flash in the time-space ether away from leaving them altogether. Busses pass me, fences hem me, the road is straight and wide, and my feet continue to move deliberately underneath me, supporting the motion of limbs and mind, the exercise of vision and thinking and hearing and being, all at once, twisting and turning through a world of lost souls and broken hearts. There is only the light that still comes down green through the trees, the angle growing flatter with passing minutes, the sound of shoes on the pavement, left, right, left. Right. And the chest heaves in recognition of the beginning, as if just now feeling the collective weight of trip and telling the body and the mind to stop, STOP, stop. Lost in one place, found in all the others.

Sunday, December 16, 2007

Running on Fumes

As we march deliberately into the end of the era of the United States as hegemonic world power like so many lemmings over the edge of a cliff, the government and the rich people keep telling us that nothing is wrong. For most people, that's enough.

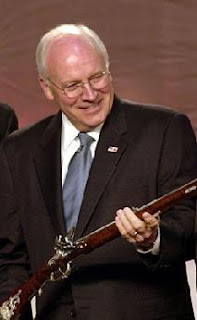

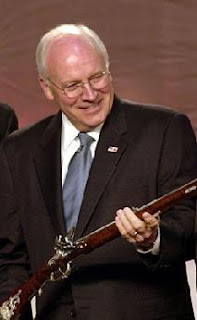

Since the abandonment of the gold standard during the era of New Deal reforms, the economy has been slipping steadily into an insurmountable hole, or debt and write-downs and outsourcing that is beginning to catch up with us. And we stand now poised at the precipice of a collapsing world financial infrastructure, looking straight down the barrel of a gun loaded with international fiscal ruin - and with Dick Cheney behind the sights that's a dangerous proposition. As far as I'm concerned, it might be the best thing that happens to humanity in my lifetime.

The steadily increasing national debt, now standing around $9 trillion is only the least of our problems. The concept itself is a quagmire, explainable only in jumbled economic jargon and a long discussion about modern monetary theory. But strip off all the bullshit and the idea is simple: we're using money that only kinda sorta actually exists on a material basis. And we're using lots and lots and lots of it. Since the advent of the Reagan revolution we've been trapped in a continuous reaffirmation of Keynesian insanity - the notion that supply-side economics was ever going to work is interminably couched in a system of privilege and inequality that knows no bounds. Giving to the poor by giving to the rich? Seriously?

In the meantime, we've deregulated almost every industry, gutted the environmental reforms of the 1970s (which made us then, unlike now, a world leader on the subject), corporatized the media, opened the revolving door between Washington, K Street lobbies, interest groups, and the private sector, ruined Social Security and subverted the Health Care system, made a mockery of mental health and veterans benefits, clamped down on immigration while opening loopholes for immigrants' exploitation, and gotten to the point where the President can hand out military contracts to his buddies in the context of an un-endable, un-winnable, extremely profitable war. I think we're doing terribly, to be honest.

Add to this the fact that even the most astutely realist political scientists agree on the fact that China's economy will be larger than ours in the next fifty years and the fact that we currently operate on a 300 million dollar-a-year trade deficit with that country and the picture gets grimmer. India isn't far behind. What's left is an America trying to retain the world heavyweight belt by force instead of retiring gracefully and changing the nature of the sport. It's like we have the choice to be Ali or Tyson and instead of thinking it over we've bitten off the ears of everyone who even sniffs in our direction the wrong way. Instead of stepping down and encouraging mutual competition, we are the bully who has been outnumbered and continues to talk shit. And we all know what happens to that guy.

If we could only stop now and try to mend the mistakes of the past instead of rewriting the Monroe doctrine and stealing from third world countries in a last ditch attempt to line our pockets we might realize that there is something altogether more important at stake than being the world's strongest nation-state: being the world's smartest. Aside from the fact that kids in America are, on average, dumber and fatter than their European, Australian, and South American counterparts (do a little looking on this), the country as a whole is missing a great opportunity to use the last gasp of our cultural influence (America as a culture is still cool, apparently) to create a worldwide movement of tolerance and subsistence instead of division and consumption, we might just manage to tip the scales back to neutral, especially on the environmental question.

The nature of international politics, as any PoliSci professor over 50 will tell you, is anarchic, unpredictable and violent. But this assumes that politics and the international system have some specific nature that dictates them instead of realizing that the whole fucking discipline is less than a few hundred years old and that a lot has changed even in the last 20 years. Imagine an international politics that involves white kids and brown kids thousands of miles away playing the same videogames on a worldwide invisible network, talking to each other in real time as they interact in a virtual world. Fuck anarchic, this shit is incredible. In the context of a world where that goes on everyday, telling me that we didn't sign Kyoto because of differences in linguistic understanding and policy restrictions is a slap in the face. Why won't we act like normal human beings that live in a finite world for once? This is our children's future.

The simple answer is deafening and silencing at once, and it crushes the spirit of those of us who see more clearly (or perhaps more vaguely). The simple answer is that a few people are making a lot of money, and they don't want to stop making that much money. And what's worse, they can't be blamed. They live in a system that constantly requires them to preform a simple and never-ending task - make more money. And he we stand, faced with the realization that the system we live in is fundamentally opposed to our material reality, a reality that includes a dwindling oil supply, a skyrocketing debt, a mortgage and credit crisis, rampant poverty and unemployment, and a planet that is screaming at the top of its poisoned lungs for us to slow the fuck down. But the engines of the system are churning along full tilt, all cylinders firing, churning liquid capital out of the earth as the economy sucks in fresh dollars out of thin air.

Simple physics tells us that combustion engines need three things: fuel, air, and ignition. The system has plenty of sparks to go around - nationalism, the American dream, stuff upon stuff upon stuff. But what happens with the oil runs out and the mystical, airborne mint breathes its last dollar bill? We all seem to know the answer, somewhere between our hearts and our stomachs, and yet we remain defiant, our foot stamped on the accelerator as we grind down the gearbox, doing 95 in a 60 in 3rd gear. I hope we have the sense to hit the brakes before its too late. But right now, it looks like I'd better get ready to tuck and roll.

Since the abandonment of the gold standard during the era of New Deal reforms, the economy has been slipping steadily into an insurmountable hole, or debt and write-downs and outsourcing that is beginning to catch up with us. And we stand now poised at the precipice of a collapsing world financial infrastructure, looking straight down the barrel of a gun loaded with international fiscal ruin - and with Dick Cheney behind the sights that's a dangerous proposition. As far as I'm concerned, it might be the best thing that happens to humanity in my lifetime.

The steadily increasing national debt, now standing around $9 trillion is only the least of our problems. The concept itself is a quagmire, explainable only in jumbled economic jargon and a long discussion about modern monetary theory. But strip off all the bullshit and the idea is simple: we're using money that only kinda sorta actually exists on a material basis. And we're using lots and lots and lots of it. Since the advent of the Reagan revolution we've been trapped in a continuous reaffirmation of Keynesian insanity - the notion that supply-side economics was ever going to work is interminably couched in a system of privilege and inequality that knows no bounds. Giving to the poor by giving to the rich? Seriously?

In the meantime, we've deregulated almost every industry, gutted the environmental reforms of the 1970s (which made us then, unlike now, a world leader on the subject), corporatized the media, opened the revolving door between Washington, K Street lobbies, interest groups, and the private sector, ruined Social Security and subverted the Health Care system, made a mockery of mental health and veterans benefits, clamped down on immigration while opening loopholes for immigrants' exploitation, and gotten to the point where the President can hand out military contracts to his buddies in the context of an un-endable, un-winnable, extremely profitable war. I think we're doing terribly, to be honest.

Add to this the fact that even the most astutely realist political scientists agree on the fact that China's economy will be larger than ours in the next fifty years and the fact that we currently operate on a 300 million dollar-a-year trade deficit with that country and the picture gets grimmer. India isn't far behind. What's left is an America trying to retain the world heavyweight belt by force instead of retiring gracefully and changing the nature of the sport. It's like we have the choice to be Ali or Tyson and instead of thinking it over we've bitten off the ears of everyone who even sniffs in our direction the wrong way. Instead of stepping down and encouraging mutual competition, we are the bully who has been outnumbered and continues to talk shit. And we all know what happens to that guy.

If we could only stop now and try to mend the mistakes of the past instead of rewriting the Monroe doctrine and stealing from third world countries in a last ditch attempt to line our pockets we might realize that there is something altogether more important at stake than being the world's strongest nation-state: being the world's smartest. Aside from the fact that kids in America are, on average, dumber and fatter than their European, Australian, and South American counterparts (do a little looking on this), the country as a whole is missing a great opportunity to use the last gasp of our cultural influence (America as a culture is still cool, apparently) to create a worldwide movement of tolerance and subsistence instead of division and consumption, we might just manage to tip the scales back to neutral, especially on the environmental question.

The nature of international politics, as any PoliSci professor over 50 will tell you, is anarchic, unpredictable and violent. But this assumes that politics and the international system have some specific nature that dictates them instead of realizing that the whole fucking discipline is less than a few hundred years old and that a lot has changed even in the last 20 years. Imagine an international politics that involves white kids and brown kids thousands of miles away playing the same videogames on a worldwide invisible network, talking to each other in real time as they interact in a virtual world. Fuck anarchic, this shit is incredible. In the context of a world where that goes on everyday, telling me that we didn't sign Kyoto because of differences in linguistic understanding and policy restrictions is a slap in the face. Why won't we act like normal human beings that live in a finite world for once? This is our children's future.

The simple answer is deafening and silencing at once, and it crushes the spirit of those of us who see more clearly (or perhaps more vaguely). The simple answer is that a few people are making a lot of money, and they don't want to stop making that much money. And what's worse, they can't be blamed. They live in a system that constantly requires them to preform a simple and never-ending task - make more money. And he we stand, faced with the realization that the system we live in is fundamentally opposed to our material reality, a reality that includes a dwindling oil supply, a skyrocketing debt, a mortgage and credit crisis, rampant poverty and unemployment, and a planet that is screaming at the top of its poisoned lungs for us to slow the fuck down. But the engines of the system are churning along full tilt, all cylinders firing, churning liquid capital out of the earth as the economy sucks in fresh dollars out of thin air.

Simple physics tells us that combustion engines need three things: fuel, air, and ignition. The system has plenty of sparks to go around - nationalism, the American dream, stuff upon stuff upon stuff. But what happens with the oil runs out and the mystical, airborne mint breathes its last dollar bill? We all seem to know the answer, somewhere between our hearts and our stomachs, and yet we remain defiant, our foot stamped on the accelerator as we grind down the gearbox, doing 95 in a 60 in 3rd gear. I hope we have the sense to hit the brakes before its too late. But right now, it looks like I'd better get ready to tuck and roll.

Wednesday, December 12, 2007

Democracy of Misrepresentation

Stop trying to figure out who's going to win the election this year. It doesn't matter.

As of right now, the imperialist swine that dictate campaign finance and strategy (read: Karl Rove) have your nuts in a fucking vicegrip. The democracy has been taken over by the hegemony of propaganda. You no longer control your own destiny.

It may sound like a bit much, but the truth remains: the voters are now, more than ever, a market to be cornered instead of served. Manipulation of media and word wars between Yale-educated system pawns dictate the flow of information, deciding what voters see, hear, think. And while the YouTube debates are certainly a step in the right direction, for the most part we are doomed to live in the blackhole of reliance on mainstream media instead of the golden age of oration. We have little or no idea what any of these candidates will do once in office, and we must realize the limiting factors of the office itself. A President, though influential, cannot change the system.

A bunch of old white guys still make laws for a country that is harly old, or white, or male. The representative democracy the United States has always claimed has always been a democracy of representation - representation of freedom, of wealth, of equality. But on the ground these things take on different guises and meanings, become entirely different things. Tell a businessman in the suburbs he's a free man and he'll tell you he knows; tell a migrant worker in Texas the same thing and he'll scowl at your hubris. Policy and politics and language mean nothing on the ground, and the beat of work and of the sun reminds our worker just how far from Washington he is, and just how far Washington is from him.

The unspoken arrangement of politics in this country is simple: we know better than you. We know the way the world works, we know the how to manipulate it, we know what's best for America. We know because we are white, and male, and rich. We know because we sat in classrooms and listened to people like us. We know because we got jobs working for people like us. And we know because of the money we've made off of people like you.

Make no doubt about it, the power elites understand this relationship. Politicians know that their power is couched in the denial of agency. CEO's know their fortune is couched in the exploitation of labor. And oil companies know their future is couched in the rape of the environment. They understand the way their world works - as a zero sum game. One up means one down, and more often two or three or ten down.

So as you watch this election season, perhaps the most ridiculous of all time, remember that you are a target. You are a consumer, a piece of the market to be cornered and exploited. You are put into groups based on race and gender and class and religion; a demographic and a number and nothing near a human being. Whether you purchase Romney or Clinton or Guiliani or Obama or, God willing, Huckabee, remind yourself that your vote comes at a price. And if you choose to be apathetic, at least do so with passion.

As of right now, the imperialist swine that dictate campaign finance and strategy (read: Karl Rove) have your nuts in a fucking vicegrip. The democracy has been taken over by the hegemony of propaganda. You no longer control your own destiny.

It may sound like a bit much, but the truth remains: the voters are now, more than ever, a market to be cornered instead of served. Manipulation of media and word wars between Yale-educated system pawns dictate the flow of information, deciding what voters see, hear, think. And while the YouTube debates are certainly a step in the right direction, for the most part we are doomed to live in the blackhole of reliance on mainstream media instead of the golden age of oration. We have little or no idea what any of these candidates will do once in office, and we must realize the limiting factors of the office itself. A President, though influential, cannot change the system.

A bunch of old white guys still make laws for a country that is harly old, or white, or male. The representative democracy the United States has always claimed has always been a democracy of representation - representation of freedom, of wealth, of equality. But on the ground these things take on different guises and meanings, become entirely different things. Tell a businessman in the suburbs he's a free man and he'll tell you he knows; tell a migrant worker in Texas the same thing and he'll scowl at your hubris. Policy and politics and language mean nothing on the ground, and the beat of work and of the sun reminds our worker just how far from Washington he is, and just how far Washington is from him.

The unspoken arrangement of politics in this country is simple: we know better than you. We know the way the world works, we know the how to manipulate it, we know what's best for America. We know because we are white, and male, and rich. We know because we sat in classrooms and listened to people like us. We know because we got jobs working for people like us. And we know because of the money we've made off of people like you.

Make no doubt about it, the power elites understand this relationship. Politicians know that their power is couched in the denial of agency. CEO's know their fortune is couched in the exploitation of labor. And oil companies know their future is couched in the rape of the environment. They understand the way their world works - as a zero sum game. One up means one down, and more often two or three or ten down.

So as you watch this election season, perhaps the most ridiculous of all time, remember that you are a target. You are a consumer, a piece of the market to be cornered and exploited. You are put into groups based on race and gender and class and religion; a demographic and a number and nothing near a human being. Whether you purchase Romney or Clinton or Guiliani or Obama or, God willing, Huckabee, remind yourself that your vote comes at a price. And if you choose to be apathetic, at least do so with passion.

Sunday, September 30, 2007

Less Decadent, More Depraved : NASCAR and The Great American Spectacle

So we're allmost out of oil. And carbon emmissions from petroleum burning engines are destroying the environment. But we're America, so we do the only logical thing: we build 800 horsepower, fuel guzzling racecars, and have them chase each other around a glorified hampster wheel for 400 laps at a time. We do it every weekend (3 times every weekend, actually), and 150,000 people come to watch.

That's three colliseums' worth of people - and the comparison is no mistake. In many ways the NASCAR phenomenon is akin to the spectacles of ancient Rome, spectacles where human life was regularly destroyed in the name of visceral entertainment. While the possibility of death, or at least the anticipation of disastrous high-speed collisions, is certainly a major draw for many fans, the sacrifice in NASCAR comes from the bosom of of Mother Nature. By most accounts, an average NASCAR series season comsumes about 200,000 gallons of fuel. This figure excludes practice, qualifying, and tuning, all of which undoubtedly inflate it considerably. The consumption itself is staggering, to be sure, but the rate at which these machines suck down gas is matched in intensity only by the jet-engine-level noise they throw into the atmosphere. The shit is loud. Really loud. Ears-bleeding, eyeballs-bulging, rib-shaking loud.

In fact, the experience of the racetrack is blistering for all five senses. Not only is your auditory capacity at the complete mercy of these massive, churning dynamos, the smell of burning rubber and Marlboros stuffs your nostrils, the cold, damp touch of a sweating Budweiser can preoccupies he fingers. And then the sights - oh the sights! Jean shorts and flame-tagged hats, no-name hightops and decaled pickups, meth addicts, swingers, smokers, mullets, spare rib and hamburger profilgacy, small children and old ladies, beer bellies and big titties, booze upon booze upon booze upon booze, more booze, a strikingly high number of full families, and a surprisingly low contingent of police. And caucasia everywhere.

They are 150,000 pilgrims to the high altar of motorsports, and on sunny Sunday sabbaths they trade in church for, as one pre-event prayer read, "racing in the name of Jesus Christ, the way God intended." And for many the spectacle is nothing short of a religious happening. Mom, Dad, and Grandma show up in the RV on Thursday night, watch qualifying, the truck race, the Busch race, and then gear up for the main event, the consecration of the entire ceremony, the culminating act of the whole shebang: the Nextel race.

Nextel races draw, on average, more spectators than for any other major sport in the United States. They command the second position, behind NFL football, in the television ratings battle. And watching a race, either in person or on that magical talking box Americans love so much, one is exposed to unparalleled volume of corporate sponsorship. Alcohol manufacturers, car insurance dealers, office suppliers, home-improvement stores, and even the US National Guard claim primary sponsorship of a Nextel car, a billion dollar a year commitment. Their logos displayed prominently on all sides of the vehicle, creating a permanent, three-hour long TV spot and a mobile billboard at the same time. Merchandise sales routinely top $2 billion annually, everything from model cars to clothing to furniture.

So why do they come? Why do these people tune in and turn out 40 weeks of the year to this fuel-wasting, environment draining, consumerism-inciting spectacle of excess and incest? They do it because the human animal is addicted to entertainment, compelled naturally toward the possibility of destruction, still governed, at some level, by the craving for viceral stimuli. And Goddamn it, dem cars go real fast.

That's three colliseums' worth of people - and the comparison is no mistake. In many ways the NASCAR phenomenon is akin to the spectacles of ancient Rome, spectacles where human life was regularly destroyed in the name of visceral entertainment. While the possibility of death, or at least the anticipation of disastrous high-speed collisions, is certainly a major draw for many fans, the sacrifice in NASCAR comes from the bosom of of Mother Nature. By most accounts, an average NASCAR series season comsumes about 200,000 gallons of fuel. This figure excludes practice, qualifying, and tuning, all of which undoubtedly inflate it considerably. The consumption itself is staggering, to be sure, but the rate at which these machines suck down gas is matched in intensity only by the jet-engine-level noise they throw into the atmosphere. The shit is loud. Really loud. Ears-bleeding, eyeballs-bulging, rib-shaking loud.

In fact, the experience of the racetrack is blistering for all five senses. Not only is your auditory capacity at the complete mercy of these massive, churning dynamos, the smell of burning rubber and Marlboros stuffs your nostrils, the cold, damp touch of a sweating Budweiser can preoccupies he fingers. And then the sights - oh the sights! Jean shorts and flame-tagged hats, no-name hightops and decaled pickups, meth addicts, swingers, smokers, mullets, spare rib and hamburger profilgacy, small children and old ladies, beer bellies and big titties, booze upon booze upon booze upon booze, more booze, a strikingly high number of full families, and a surprisingly low contingent of police. And caucasia everywhere.

They are 150,000 pilgrims to the high altar of motorsports, and on sunny Sunday sabbaths they trade in church for, as one pre-event prayer read, "racing in the name of Jesus Christ, the way God intended." And for many the spectacle is nothing short of a religious happening. Mom, Dad, and Grandma show up in the RV on Thursday night, watch qualifying, the truck race, the Busch race, and then gear up for the main event, the consecration of the entire ceremony, the culminating act of the whole shebang: the Nextel race.

Nextel races draw, on average, more spectators than for any other major sport in the United States. They command the second position, behind NFL football, in the television ratings battle. And watching a race, either in person or on that magical talking box Americans love so much, one is exposed to unparalleled volume of corporate sponsorship. Alcohol manufacturers, car insurance dealers, office suppliers, home-improvement stores, and even the US National Guard claim primary sponsorship of a Nextel car, a billion dollar a year commitment. Their logos displayed prominently on all sides of the vehicle, creating a permanent, three-hour long TV spot and a mobile billboard at the same time. Merchandise sales routinely top $2 billion annually, everything from model cars to clothing to furniture.

So why do they come? Why do these people tune in and turn out 40 weeks of the year to this fuel-wasting, environment draining, consumerism-inciting spectacle of excess and incest? They do it because the human animal is addicted to entertainment, compelled naturally toward the possibility of destruction, still governed, at some level, by the craving for viceral stimuli. And Goddamn it, dem cars go real fast.

Thursday, June 7, 2007

To: Anonymous - From: The Kids

From the kids of the street:

Fuck you nigga.

You heard me.

Fuck you, Nigga.

Wow nigga

how nigga

now nigga

tell me how i'm supposed to rise above the violence and strife

when the smell around me cuts like a knife

when none of the my brothers' fathers call my mother their wife

when the game pins my ambition tight like a vice

tell me how i'm supposed to live my life.

school's out prison's in

it's where i'll find my closest of kin

doin time in the joint for smokin' a joint

mothafuckas i know you got my point man

held up in cuffs like scotland yard

playin' the trump card; rat

me out i'm beggin you please

my homies'll have screamin 'don't' from your knees

just be thankful i'm smokin' those trees

make 5.50 to work, lose 10 from welfare

you do the math like sebastian telfar,

couldn't count the numbers on the fuckin' contract

even if he could make the shot after contact.

so hedge fund your bets trustfunders

and let the system pull me under

pregnant by 15, addicted at 20, dead at 40,

damn sure MY record never made no royalties

still holdin tight in my pocket to my false sense of loyalty

to the streets.

so fuck you nigga.

you heard me.

fuck you, nigga

- the youth

Fuck you nigga.

You heard me.

Fuck you, Nigga.

Wow nigga

how nigga

now nigga

tell me how i'm supposed to rise above the violence and strife

when the smell around me cuts like a knife

when none of the my brothers' fathers call my mother their wife

when the game pins my ambition tight like a vice

tell me how i'm supposed to live my life.

school's out prison's in

it's where i'll find my closest of kin

doin time in the joint for smokin' a joint

mothafuckas i know you got my point man

held up in cuffs like scotland yard

playin' the trump card; rat

me out i'm beggin you please

my homies'll have screamin 'don't' from your knees

just be thankful i'm smokin' those trees

make 5.50 to work, lose 10 from welfare

you do the math like sebastian telfar,

couldn't count the numbers on the fuckin' contract

even if he could make the shot after contact.

so hedge fund your bets trustfunders

and let the system pull me under

pregnant by 15, addicted at 20, dead at 40,

damn sure MY record never made no royalties

still holdin tight in my pocket to my false sense of loyalty

to the streets.

so fuck you nigga.

you heard me.

fuck you, nigga

- the youth

Wednesday, May 23, 2007

Why Hip-Hop Is Better Than Government

Spits straight, gains weight, won't take your claim, shit on your game, take aim at your will.

No, hip-hop won't hate, won't comiserate with these fools at the gates with these cats, straight house cats not wiling to go and see the results of their elite complicity, the ghettos full of kids left behind and junkies in a bind, sleepin' on the streets while the politicians' daughters win track meets.

Hip-hop can't classify, identify, indemnify the causes of the american poverty, the highs in white houses spitting lies at black faces, forgetting the truth about people in places, constantly avoiding all incriminating traces, denying different races play a role when the dark-skinned ones are the only ones that they stole.

Hip-hop won't judge and won't budge, holds deserved grudges and has its own judges, taking cases to street over soul-inspired beats, speaks to those who listen and listens to those that speak, evolves of the mind and never abandons the grind, working hard for effortless flows, from the cypher to the show, takes you as you come and may never let you go.

Hip-hop is the meditation of the mind, a divine contraception of ideas and reception, the confluence of lessons learned in long private sessions, with friends and L's moving in procession to the beat, the beat, the beat of impression that never preaches down to the masses but comes up with the grasses between the concrete blocks of the world that walks.

Hip-hop don't charge taxes, it relaxes, the body and mind at the same pace, sayin' grace to the pioneers of street lure and emcees of rap galore, spreading the rhetoric of a new asthetic in rhymes and sayin' fuck it to the times, fuck it to the lines of propaganda bullshit, fuck it to the last of this too long BUSH-shit, fuck it to the congress and courts that try to save, all they've done is re-enslave.

Hip-hop is better than government.

No, hip-hop won't hate, won't comiserate with these fools at the gates with these cats, straight house cats not wiling to go and see the results of their elite complicity, the ghettos full of kids left behind and junkies in a bind, sleepin' on the streets while the politicians' daughters win track meets.

Hip-hop can't classify, identify, indemnify the causes of the american poverty, the highs in white houses spitting lies at black faces, forgetting the truth about people in places, constantly avoiding all incriminating traces, denying different races play a role when the dark-skinned ones are the only ones that they stole.

Hip-hop won't judge and won't budge, holds deserved grudges and has its own judges, taking cases to street over soul-inspired beats, speaks to those who listen and listens to those that speak, evolves of the mind and never abandons the grind, working hard for effortless flows, from the cypher to the show, takes you as you come and may never let you go.

Hip-hop is the meditation of the mind, a divine contraception of ideas and reception, the confluence of lessons learned in long private sessions, with friends and L's moving in procession to the beat, the beat, the beat of impression that never preaches down to the masses but comes up with the grasses between the concrete blocks of the world that walks.

Hip-hop don't charge taxes, it relaxes, the body and mind at the same pace, sayin' grace to the pioneers of street lure and emcees of rap galore, spreading the rhetoric of a new asthetic in rhymes and sayin' fuck it to the times, fuck it to the lines of propaganda bullshit, fuck it to the last of this too long BUSH-shit, fuck it to the congress and courts that try to save, all they've done is re-enslave.

Hip-hop is better than government.

Thursday, April 26, 2007

The New Democracy: Government on the People, at the Cost of the People.

Get out the champagne, crack that bottle you've been holding on to, smoke that secret stash you've been saving. I figured it out. I figured out how to fix Iraq.

1). Invade the country for no reason, with no evidence, and with a wafer-thin authorization from Congress.

2). Create a Public Relations campaign the likes of which America has never seen; a propaganda circus that includes fake news, embedded censorship, and an unrelenting assault of false statements.

3). Proclaim a premature victory to rouse nationalism against the barbarians.

4). Send a whole bunch of able-bodied American men to be killed. (But try to take the poor, the brown, the uneducated, marginalized. We never liked the fuckers anyways.)

5) Award billions of dollars of military contracts to your buddies. Cuz fuck 'em, why not?

6). Try to institute a democratic, power-sharing government in a country that has never seen power-sharing, democracy, or government. Oh, and we destroyed the entire infrastructure. No more moads, policing, sewers, drinking water, airports, banking. Our bad. But hey, more contracts for your buddies.

7). When the American people find out what's going on, silence the dissenters. If the war is good against evil, only the hippies will pick evil. And remember, God Loves the Patriot Act.

8). Build a wall in the middle of Baghdad to separate the two sides. We know building walls to separate people works really well. Just look at Germany, Palestine, and Northern Ireland.

9). Fight to the death to keep the troops in Iraq, to the point of absurdity. 3,000 are already dead, what's another 500? Americans won't remember in five years anyways, right?

10). Get the hell out of dodge. Go find yourself a nice ranch in Texas. Smoke those Cubans the CIA stole from Fidel, blow that coke you extorted from the Medellin, drink that bottle of vodka you scammed from Putin and the Scotch Tony Blair gave you to let him suck you off. And while you're at it, fuck that 15 year-old virgin the bin-Ladens gave you to 'make this whole thing go away.'

What's that you say? It didn't work? Iraq is still a disaster? Well, fuck 'em. You're rich.

Monday, April 23, 2007

An Audience of One

From the start, let it be clear that any undue loss of life, no matter how small or large, is a crime and a tragedy. To force someone else to unwillingly lose their life is to rob them of their future children, their future loves, their future professions, their future hopes and aspirations - in short, the future.

So when we come face to face with death on such a large scale as the recent events at Virginia Tech, we must, absolutely, take pause to reflect upon the state of a world that allows such things to go on. We must examine the structures that support a worldview like the one that caused the death of 32 innocent students. And of course, we must grieve over the loss of a pool of human resources so wide and deep it can never be recreated. But in this reflection we must be honest about the ways of the world and try to look at the underlying causes and power structures that harbor violence within their ideological walls.

As the media coverage has rolled on, nearly ubiquitously, the solutions to problems like this have been simple: increase security, provide counseling, try to screen for disturbed youth. In short, the answer has been more guns, not less. The answer has been to increase security, not to decrease hate. The answer, American as America gets, is more and more and more instead of simply better. And as the media continues to broadcast from Virginia Tech and continues to show the manifesto tape of the killer, we are confronted with yet another truth: this is exactly what he wanted.

The shooter credits the two young men from Columbine High School as "martyrs" in his taped remarks, a sign of the increasing allegiance to violence as the means of escape from a culture of hate and degradation that follows many adolescents. What made this student so angry was the affluence and entitlement that surrounded him, the feeling of unnacceptance that comes with being a brown person in a white country, the sense that everyone around him was the recipient of a divine grace that he missed. In short, he was seduced by the great American myth of more and not better, unaware that many of the affluent and entitled students he was seeing through angry eyes were the victims of the same dissafection.

But the point here is that he had a model to follow. Columbine, as the firestarter that ignited a trend of school shootings, painted a picture of the rebels that stuck in the minds of others. All over the country, students from high school to elementary school were bombarded by the images of the two shooters in trenchcoats, enacting their revenge upon the popular, the wealthy, the entitled, the authorities. All over the country, students watched blueprints and timelines and examined every aspect of the incident, from the weapons technology to the manifesto to Marilyn Manson. And suddenly, all over the country, students who felt the same way had an example.

As we are faced with a tragedy that matches Columbine in scale, why are we doing the same things? Instead of diagramming the hallways and remarking the shooter's expert marksmanship, why are we not interviewing students who aren't letting this violence affect their lives? Why, instead of silencing the voice of violent oppression, are we giving it primetime media coverage. The end message is this: "if you feel silenced, or oppressed, or disenfranchised, and you want to do something about it, violence will give you a voice. Violence will lead the way. Violence will help you reach an audience of half a billion people." Thirty-two students later, this shooter got what he wanted all along: a voice.

By all means, we must protect ourselves. But we must do so in the manner that makes the most sense: by listening. There are other student out there who are watching and learning, others who feel the way this student did. And though there is a difference between feeling and action, that difference can be erased by a single hateful comment, a single act of ignorance or malice.

So in honor of the fallen students, and in hope for the future, turn off your television and open your eyes and ears. With an honest desire to listen and learn instead of fear and loathe, you might just stop the shooting.

So when we come face to face with death on such a large scale as the recent events at Virginia Tech, we must, absolutely, take pause to reflect upon the state of a world that allows such things to go on. We must examine the structures that support a worldview like the one that caused the death of 32 innocent students. And of course, we must grieve over the loss of a pool of human resources so wide and deep it can never be recreated. But in this reflection we must be honest about the ways of the world and try to look at the underlying causes and power structures that harbor violence within their ideological walls.

As the media coverage has rolled on, nearly ubiquitously, the solutions to problems like this have been simple: increase security, provide counseling, try to screen for disturbed youth. In short, the answer has been more guns, not less. The answer has been to increase security, not to decrease hate. The answer, American as America gets, is more and more and more instead of simply better. And as the media continues to broadcast from Virginia Tech and continues to show the manifesto tape of the killer, we are confronted with yet another truth: this is exactly what he wanted.

The shooter credits the two young men from Columbine High School as "martyrs" in his taped remarks, a sign of the increasing allegiance to violence as the means of escape from a culture of hate and degradation that follows many adolescents. What made this student so angry was the affluence and entitlement that surrounded him, the feeling of unnacceptance that comes with being a brown person in a white country, the sense that everyone around him was the recipient of a divine grace that he missed. In short, he was seduced by the great American myth of more and not better, unaware that many of the affluent and entitled students he was seeing through angry eyes were the victims of the same dissafection.

But the point here is that he had a model to follow. Columbine, as the firestarter that ignited a trend of school shootings, painted a picture of the rebels that stuck in the minds of others. All over the country, students from high school to elementary school were bombarded by the images of the two shooters in trenchcoats, enacting their revenge upon the popular, the wealthy, the entitled, the authorities. All over the country, students watched blueprints and timelines and examined every aspect of the incident, from the weapons technology to the manifesto to Marilyn Manson. And suddenly, all over the country, students who felt the same way had an example.

As we are faced with a tragedy that matches Columbine in scale, why are we doing the same things? Instead of diagramming the hallways and remarking the shooter's expert marksmanship, why are we not interviewing students who aren't letting this violence affect their lives? Why, instead of silencing the voice of violent oppression, are we giving it primetime media coverage. The end message is this: "if you feel silenced, or oppressed, or disenfranchised, and you want to do something about it, violence will give you a voice. Violence will lead the way. Violence will help you reach an audience of half a billion people." Thirty-two students later, this shooter got what he wanted all along: a voice.

By all means, we must protect ourselves. But we must do so in the manner that makes the most sense: by listening. There are other student out there who are watching and learning, others who feel the way this student did. And though there is a difference between feeling and action, that difference can be erased by a single hateful comment, a single act of ignorance or malice.

So in honor of the fallen students, and in hope for the future, turn off your television and open your eyes and ears. With an honest desire to listen and learn instead of fear and loathe, you might just stop the shooting.

Monday, April 9, 2007

Thursday, March 29, 2007

Bush-Shit

Congress today approved another $95.7 billion for the continued efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan. This appropriation, were it to stand alone, would put it just ahead of Egypt for the 52nd largest GDP of any nation in the world. Stand and think about that for a second. In the stroke of just a few minutes, a bunch of old white guys just gave away the 52nd largest economy in the world.

President Bush - who should, by now, have been given another title, something closer to Furor - has threatened to veto the bill because it involves a timeline for troop withdrawl. Likely, he will veto it. His remarks today, as quoted in the New York Times, are stunning: "We stand united in saying loud and clear that when we’ve got a troop in harm’s way, we expect that troop to be fully funded. And we’ve got commanders making tough decisions on the ground, we expect there to be no strings on our commanders. And that we expect the Congress to be wise about how they spend the people’s money."

I have this to say: FUCK YOU, Mr. Bush.

In the last seven years we've seen you constantly undermine the workings of American government and subvert all it means to be the democratic leader of a free state. We've seen you rig elections. We've seen you steal from the American people to profit your cronies. We've seen you dismantle the Geneva Convention, Social Security, free speech, and habeas corpus. We've seen you lie to us time and time again. We've seen you do nothing while thousands of people were stranded in an unlivable swamp. We've seen you hand out positions to those who were willing to take your word as law, and we've seen you summarily terminate all those who don't. We've seen you smirk, and smile, and chuckle about "the haves and the have mores." We've seen you turn your head away from torture and poverty. We've seen you and your cabinet circumvent the judicial and legislative branches in agregious breaches of the Constitution. And we've seen you make us embarrased to call you our President.

We see you, Mr. Bush, for what you are. And we've seen enough.

Tuesday, March 20, 2007

Banana Republicans

What would you say about a country whose GDP growth rate stands at 10.3%? Whose poverty rates have dropped by 10%? Whose leader has offered aid to minorities and those in poverty in foreign countries? Sounds like a good deal to me.

Now what would you say about a country who is stockpiling Soviet weapons and aircraft? Whose leader is regarded by some as the most dangerous and divisive pundit in the Western hemisphere? Who stages protests and speaks out vigorously against the most powerful country in the world?

Enter Hugo Chavez. Part revolutionary, part drama queen, part politician, the Venezuelan leader is both loved and loathed – but he rarely goes unnoticed. During President Bush’s recent visit to Latin America, Chavez made nearly as much news as the leader of the free world, staging demonstrations and events, often in close proximity to Bush’s, as a counterweight to the president’s rhetoric of human rights and strengthening relations with Latin America.

Of course, President Bush had nothing to say about Chavez, whose name he refuses to speak out loud. Chavez, who has taken to calling Bush “El Diablo” has been essentially erased from the president’s official language. After all, if you his name isn’t spoken, then he must not exist, right?

Unfortunately for the administration, Chavez does exist, and his voice is getting louder. Far from the criminal the Bush administration would like to portray him as, Chavez is the leading voice in a growing contingent of Latin American countries that are fed up with the dominance of American-based corporations in their native lands.

As most countries in Latin and South America continue to struggle to provide basic human needs for a large percentage of their citizens, the anti-poverty rhetoric of a corporate-heavy American policy becomes more and more transparent. The privatization of natural resources such as water, oil, natural gas, and (perhaps most famously) fruit has led to a trend of rising prices and constricting access for native citizens. But Chavez, working with other leaders, has begun to spread the rhetoric of change, relying on nationalism and anti-American sentiment to help incite a movement back toward national ownership.

Venezuela has nationalized its oil industry, one of the largest in the world, and it appears that others are following suit. Last year, Bolivia made the decision to nationalize its own natural gas reserves, and Colombia, despite outward statements that may suggest otherwise, has expanded production of cocoa, its largest cash crop.

But what makes Chavez and Venezuela unique is the oil. Unlike other third world leaders, Chavez is sitting on an enormous reserve of petroleum – that magic black substance the US seems to be willing to go to all ends of the earth to procure. What’s more, Venezuela remains the fourth largest importer of oil to the United States. So while the Bush administration can dismiss Chavez now as they dismiss all the others who denounce its policies, Chavez remains in control of a resource that becomes more valuable every day, especially to his gas-guzzling American opponents. It is his always ready and rarely mentioned trump card.

OIL

Last September, Chavez made a push to solidify his stance in the United States. Acting through Houston-based Citgo Corp. and in conjunction with Joe Kennedy’s Citizen’s Eneregy project, Chavez promised to provide Venezuelan oil at low cost to about 450,000 low-income families in the United States. Promoting the program at the United Nations General Assembly, he made strong remarks denouncing the consolidation of power in the highest office in the land. Responding to the claims of extremism often made by his American critics, Chavez had this to say: “The imperialists see extremists everywhere. It's not that we are extremists. It's that the world is waking up. It's waking up all over. And people are standing up.”

Yet the response to this seemingly benevolent act has run the gamut from praise to damnation, both from ordinary citizens and political figures. Arguing that the subsidies amount to nothing more than an attempt to curry favor in a disenfranchised demographic, his detractors have called for outright refusal of Venezuela. Supporters, on the other hand, praise Chavez for his ability to see human need ahead of financial gain.

Despite the contentiousness of the action, Venezuelan oil, subsidized or not, continues to pour into the United States. According to PDVSA, Venezuela’s state-owned oil firm, Venezuela plans to expand production to nearly 3.5 million barrels a day this year, with an estimated 50% of the total yield flowing directly into the United States.

“If discounted fuel from Venezuela is somehow unfit for the needy, the full-price Venezuela oil shouldn’t be enough for the cars, boats, jets and furnaces of the wealthy,” said Kennedy. In the U.S., where federal assistance for programs like Citizen’s Energy that provide low-cost heating fuel has been cut drastically during the Bush administration, the incentive for refusing Chavez’s oil seems low.

But in Alaska, another targeted location of CITGO’s low-cost oil initiative, some citizens are speaking out. Letters in the Anchorage Daily News express the sentiments from those who are less than grateful for the donation of Venezuelan oil. One resident called for those who accept the oil to “no longer be accepted as U.S. citizens.” Others aim for the heart, like Alexander Clark of Homer, Alaska: “There are many brave and proud rural Alaskans wearing the uniform of this country who are engaged in combat with the very enemy that Chavez supports. How proud of you will they be?”

Clark’s admonition is a common one, and the belief that Chavez is allied with destructive forces around the world is not entirely unfounded. He has developed relationships with both Syria and Iran and defended the rights to nuclear armament of the latter. He is widely known to revere Fidel Castro as a model of anti-American resistance, and was the sole world leader to visit Saddam Hussein in 1991. Though there appear to be no explicit links between Chavez and known terrorist organizations, the implications abound. Marked by dense vegetation and a lack of organized government presence, parts of Venezuela, especially those along the Colombian border, are suspected areas of “narco-terrorist” activity stemming from the production of cocaine and other narcotics. Despite the irony that these activities are fueled primarily by demand from the United States, these connections have prompted the U.S. State Department to label Venezuela a “liability” in the “international community’s fight against terrorism.”

Yet in the era of an administration that has used strangely similar language as a basis for the invasion and sanctioning of other resource-rich countries, the admonition bears little weight. The oil industry and its handmaidens in Washington have together created a rhetoric of terrorism against democracy, socialism against capitalism, extremism against determinism. In this light, Chavez seems only one of a multitude of targets of U.S. criticism.

“If objections to Venezuelan oil are about democracy,” said Kennedy, “then critics should look at the December elections won by President Hugo Chavez with nearly 70 percent of the vote. Venezuelans have now spoken four times in his favor.

“I'm not going to defend or demonize Chavez for his moves toward socialism, but it does seem like we favor selective socialism here in the United States for big corporations that get to socialize risks and privatize profits.”

Labels:

George W. Bush,

Hugo Chavez,

neoliberalism,

oil,

system

Wednesday, February 28, 2007

Real Quick: On Jazz

It is a strange brand of man who can appreciate the innuendos of a trumpet, muted or not - the intricacies of a well-driven bassline, soft and subtle but always present; the nuanced touch of hammers on strings created by deft hands. But the synthesis of these diversified sounds appeals, sticky sweet and musky, to the rookie and the connoisseur.

This is America's music - the precursor to soul and funk-rock, the grandfather of hip-hop, pinned up high and tight in a suit like you knew he would be but never far from his whiskey glass. This is the beat of a movement that has always existed in America and always will, the steady pulsing of a silent oppresion and the creativity it spawns. Make no doubt about it, this is Black music - but it belongs to all of us.

Miles and Yardbird, The Duke and his damsels, a Monk and a piano, Fats Waller, and the rent. Together they tell the story of generation arriving before its time, a single perfect rosebud emerging before the last frost. Destined, in a sense, to stall and die. But the jazz movement was better than that - is better than that. It makes no demands on the music, imposes no social constraints. Listen to it. It's for itself, the pure expression of an emotion no words can match. Listen. Brushing symbols and snare drums, a bass walking with swagger in its step. And then the sax, piercing and clear, just barely this side of cutting, whining and droning at the edge of the register and then coming back down to earth, setting nicely next to the drummer and setting the trumpet free. It does work.

The thing about evolution is that it doesn't necessitate the death of the formerly evolved. Jazz morphed from ragtime and be-bop and morphed into soul, and R&B, and funk-rock, and hip-hop, but it never died. It speaks still from the immortal, the heartbeat of a people and a nation, an almost forgotten but never mistaken confluence of hope and despair, solace and solidarity.

This is America's music - the precursor to soul and funk-rock, the grandfather of hip-hop, pinned up high and tight in a suit like you knew he would be but never far from his whiskey glass. This is the beat of a movement that has always existed in America and always will, the steady pulsing of a silent oppresion and the creativity it spawns. Make no doubt about it, this is Black music - but it belongs to all of us.

Miles and Yardbird, The Duke and his damsels, a Monk and a piano, Fats Waller, and the rent. Together they tell the story of generation arriving before its time, a single perfect rosebud emerging before the last frost. Destined, in a sense, to stall and die. But the jazz movement was better than that - is better than that. It makes no demands on the music, imposes no social constraints. Listen to it. It's for itself, the pure expression of an emotion no words can match. Listen. Brushing symbols and snare drums, a bass walking with swagger in its step. And then the sax, piercing and clear, just barely this side of cutting, whining and droning at the edge of the register and then coming back down to earth, setting nicely next to the drummer and setting the trumpet free. It does work.

The thing about evolution is that it doesn't necessitate the death of the formerly evolved. Jazz morphed from ragtime and be-bop and morphed into soul, and R&B, and funk-rock, and hip-hop, but it never died. It speaks still from the immortal, the heartbeat of a people and a nation, an almost forgotten but never mistaken confluence of hope and despair, solace and solidarity.

Monday, February 19, 2007

6, Uptown

“Gangstas of Gotham, hardcore hustlin’”- Mos Def

I take the 6, uptown. At 34th, the train is all white. By 59th, half of the suits are gone but caucasia still prevails in my car. After 86th, the change starts, and by 110th I’m one of two white people on the train. And this is strangely comforting.

I am a product of a Catholic, white, upper-middle class neighborhood. I went to a private boarding school in Connecticut. I go to a Jesuit school in Boston. All of these things influence my place in the world, influence the way I think and the way others think about me. I am guilty of elitism, even if I don’t know it. So when I stay on the 6 past Manhattan, headed for the Bronx, I know I don’t understand. I know I can’t fit in, can’t begin to understand the complexities of the environment that surrounds me. And when I listen to my homegirl, a teacher in Hunts Point, I can’t ever understand the problems she sees everyday.

Save my own, I don’t know anyone’s parents who were under 25 when they had children. I don’t know what it’s like to grow up in the city, to have drugs and violence around me in profusion. I don’t know what it’s like to be discriminated against by police and constantly marginalized by a government that wants to forget about me. But I can stay on the train past Manhattan, I can walk the streets of the South Bronx, I can listen with learning ears to Mos Def and Common and Nas and know, for certain, that if my life had been different I wouldn’t have been able to rise above it. But I am white, and I know I cannot understand. That is my one, incommunicable sin. I am an imposter.

The misconception of the ghetto in most Americans’ thought is that it looks scary, different, cold. That the people who live there are in some way different beyond economics, capable of different things. Bad things. That somehow ‘thugs’ are manufactured and perfected, trained as murderers and drug dealers from the start. They don’t realize that the most of the people they think about are kids, pushed into the hustle by money, excitement, and often the very people who love them most. It’s not a struggle, or a problem, or a disease – it simply is.

The man next to me on the six stands two or three inches taller than me. His beard two or three inches longer. His hair two or three shades greyer, his skin more than two or three shades darker. He’s talking to himself. I’m listening. “You think you free,” he says, “but you ain’t. Same old slaveowners, ain’t nothin’ changed. Ain’t NOTHIN’ changed. Nosah. Ain’t nothin’ changed.” No one else on the 6 pays attention. He stares out the window into darkness. He keeps talking. I listen for a long time, understanding some of it, missing most of it, but hearing every word.

“You go to school,” says the man next to me on the platform. I turn my ear and look at him as if I’ve misunderstood. “You go to school?” he repeats, this time with inquisitive inflection.

“ Yes,” I say, “in Boston.”

“Boston, oh.” He turns away. “I used to live in Lowell,” he says, and I see his smile for the first time. “Long time ago.”

We stay silent for a while. I’m in a city I don’t know. I can’t be sure of protocol when it comes to other people. Finally I give in to my curiosity. He seems affable.

“You from here originally?” I ask. He looks at me as if I’m kidding. I’m not.

“No,” says. He looks up at me and smiles, and I am struck by his balanced features and remarkably consistent skin tone. His eyes are piercing, his smile astonishing. “I am,” he pauses, “Dominicano.” He smiles broader, beaming with his declaration. I hear the word in my head for the rest of the trip. Dominicano. And what could I say with such pressing importance? What could I declare with such surety? Blanco? Gringo? Irish? Maybe. But despite my education and my economy and my freedom of movement, I won't mean it like he does.

Coming back, downtown 6, I get off at 103rd. It’s a little past 11 at night. Now, rising to street level from the stairs, I open my eyes to the darkness. It’s quieter than I would have expected, despite the figures that dot the street. At night the bustle gives way to the hustle. Eyes dart when I walk by, clearly out of place, and despite a confident walk a focused gaze I’m careful to remain carefully alert in this environment – searching the corners of darkness. Shit, I realize I’m as bad as anyone else – I’m looking for stereotypes – young black males with baggy pants and – there they are.

And there it is. They. The extension of my incommunicable sin. The other. The ghetto. I listen to the conversation as I pass.

“Damn she din’t call you back yet yo? Ya ass is done, she out right now son-” He laughs.

“Nah, s’ok. She’ll get at me, just wait. And who you waitin’ on anyways? Get outa here punk-”

They’re joshing, half laughing, sparring. In the group of four, the youngest is maybe 14, the oldest 16. At their age, my friends and I got jobs slinging papers in the neighborhood, playing and working like these guys are. The object is different, but the verb is the same. It’s what you do.

The next morning homegirl brings me to a restaurant around the corner. It’s a hallway, mostly, some tables in the front and a hot line beyond a thin curtain in the back. We order burritos and for the first time since Tijuana get what I’m looking for – a mass of shredded chicken, fresh refritos, and tart guacamole smothered in cheese and salsa verde. The tortilla is handmade. The two next to us converse in Puerto Rican Spanish, rolling and fast, shades of Portuguese and Dominican, far from the Castilian in textbooks. They get up and pay, handing the young cashier a 5 for their full meals and drinks.

We finish and approach the register, I pull out my wallet. She writes a slip, hands it to me. $15.95. I offer a 20 and smile, taking my four singles and replacing them in the fold. If only we could get the healthcare system to work like that, I think.

The problem, if we choose to think of it like that, is not the people but the system itself. Somewhere between 86th and 110th, the opportunities go away, the chances get slimmer, the obstacles bigger. Fewer people are going to make it out. It’s the difference between an invisible barrier that has nothing to do with color or heritage – only indifference and ignorance. Put me – white, male, of sound mind and body – in a project at 153rd instead of a brownstone on 65th and strip me of my education, my citizenship, my language, my income. Watch me falter and fail to get by, give up minimum wage for the risk and reward of the game. I don’t have the stock market anymore, I got the rock market – and it never goes down.

And so the 6 uptown becomes the channel that runs beneath the lines on the map, drawn in white and brown, rich and poor, that criss-cross the city, the culture, the nation, the world. It’s a conduit between two worlds, a single train that simultaneously separates and connects the down-town upper-crust with the up-town downtrodden. Opening your eyes and ears on the 6 is easy, but opening your mind to see the larger picture is imperative – you’ll see that the suit at 43rd, a lifetime New Yorker, isn’t lying when he says “ I’ve never been up that far.”

I take the 6, uptown. At 34th, the train is all white. By 59th, half of the suits are gone but caucasia still prevails in my car. After 86th, the change starts, and by 110th I’m one of two white people on the train. And this is strangely comforting.

I am a product of a Catholic, white, upper-middle class neighborhood. I went to a private boarding school in Connecticut. I go to a Jesuit school in Boston. All of these things influence my place in the world, influence the way I think and the way others think about me. I am guilty of elitism, even if I don’t know it. So when I stay on the 6 past Manhattan, headed for the Bronx, I know I don’t understand. I know I can’t fit in, can’t begin to understand the complexities of the environment that surrounds me. And when I listen to my homegirl, a teacher in Hunts Point, I can’t ever understand the problems she sees everyday.

Save my own, I don’t know anyone’s parents who were under 25 when they had children. I don’t know what it’s like to grow up in the city, to have drugs and violence around me in profusion. I don’t know what it’s like to be discriminated against by police and constantly marginalized by a government that wants to forget about me. But I can stay on the train past Manhattan, I can walk the streets of the South Bronx, I can listen with learning ears to Mos Def and Common and Nas and know, for certain, that if my life had been different I wouldn’t have been able to rise above it. But I am white, and I know I cannot understand. That is my one, incommunicable sin. I am an imposter.

The misconception of the ghetto in most Americans’ thought is that it looks scary, different, cold. That the people who live there are in some way different beyond economics, capable of different things. Bad things. That somehow ‘thugs’ are manufactured and perfected, trained as murderers and drug dealers from the start. They don’t realize that the most of the people they think about are kids, pushed into the hustle by money, excitement, and often the very people who love them most. It’s not a struggle, or a problem, or a disease – it simply is.

The man next to me on the six stands two or three inches taller than me. His beard two or three inches longer. His hair two or three shades greyer, his skin more than two or three shades darker. He’s talking to himself. I’m listening. “You think you free,” he says, “but you ain’t. Same old slaveowners, ain’t nothin’ changed. Ain’t NOTHIN’ changed. Nosah. Ain’t nothin’ changed.” No one else on the 6 pays attention. He stares out the window into darkness. He keeps talking. I listen for a long time, understanding some of it, missing most of it, but hearing every word.

“You go to school,” says the man next to me on the platform. I turn my ear and look at him as if I’ve misunderstood. “You go to school?” he repeats, this time with inquisitive inflection.

“ Yes,” I say, “in Boston.”

“Boston, oh.” He turns away. “I used to live in Lowell,” he says, and I see his smile for the first time. “Long time ago.”

We stay silent for a while. I’m in a city I don’t know. I can’t be sure of protocol when it comes to other people. Finally I give in to my curiosity. He seems affable.

“You from here originally?” I ask. He looks at me as if I’m kidding. I’m not.

“No,” says. He looks up at me and smiles, and I am struck by his balanced features and remarkably consistent skin tone. His eyes are piercing, his smile astonishing. “I am,” he pauses, “Dominicano.” He smiles broader, beaming with his declaration. I hear the word in my head for the rest of the trip. Dominicano. And what could I say with such pressing importance? What could I declare with such surety? Blanco? Gringo? Irish? Maybe. But despite my education and my economy and my freedom of movement, I won't mean it like he does.

Coming back, downtown 6, I get off at 103rd. It’s a little past 11 at night. Now, rising to street level from the stairs, I open my eyes to the darkness. It’s quieter than I would have expected, despite the figures that dot the street. At night the bustle gives way to the hustle. Eyes dart when I walk by, clearly out of place, and despite a confident walk a focused gaze I’m careful to remain carefully alert in this environment – searching the corners of darkness. Shit, I realize I’m as bad as anyone else – I’m looking for stereotypes – young black males with baggy pants and – there they are.

And there it is. They. The extension of my incommunicable sin. The other. The ghetto. I listen to the conversation as I pass.

“Damn she din’t call you back yet yo? Ya ass is done, she out right now son-” He laughs.

“Nah, s’ok. She’ll get at me, just wait. And who you waitin’ on anyways? Get outa here punk-”